Vodafone agrees to acquire Liberty Global and cements its position as leading challenger: upstart to duopolist

10 May 2018 | Research

Article | Operator Investment Strategies| Fixed–Mobile Convergence| Fibre Infrastructure Strategies

Vodafone confirmed that it has agreed to acquire Liberty Global assets in the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary and Romania for EUR18.4 billion. This are subject to regulatory scrutiny and the full deal is not expected to close for at least a year. This comment is an update to a comment that we published in February, when it was announced that Vodafone and Liberty Global were in formal talks. It focuses on the strategic positioning aspects of the deal rather than on the economic synergies.

Vodafone wants to be the leading challenger in Europe

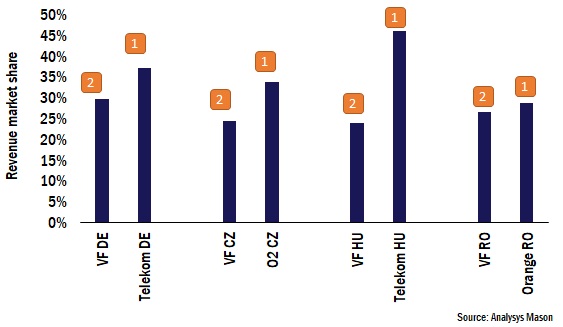

Vodafone's long-term strategy is to be the only similarly-sized European-level competitor in fixed and mobile to the incumbents, and to have the highest number of fixed–mobile converged (FMC) accounts in Europe (an ambition shared with Deutsche Telekom and Orange). Latest available figures show it is only fourth. Orange was the clear leader with 10.6 million FMC accounts in Europe (March 2018), whereas Vodafone had 4.1 million (Dec 2017). The acquisitions will make Vodafone clear number two in terms of mass-market revenue in each of the four markets (in Romania it will be second to Orange, with former incumbent Telekom third).

Figure 1: Enlarged Vodafone share of mass-market retail revenue, plus leading operator share, four countries, YE 2017

Germany

By buying UnityMedia, Vodafone would become a player of a similar scale and stature to Telekom. With increased scale in fixed comes a possible threat of more symmetrical broadband regulation, but also the possibility of deregulation. In fact, in some more-advanced European broadband markets, where the emphasis has been on infrastructure-based competition, more symmetrical commercial arrangements between fibre network owners have emerged anyway (for example, access swapping in Portugal, commercial wholesale in Spain).

Telekom opposes the German acquisition, ostensibly on the grounds of pay-TV concentration. In the past, Telekom owned all the cable networks to the building, but was forced to sell them. The pay-TV market is more susceptible than that of broadband to quick disruption: from pure all-IP plays of the international Netflix kind, from Sky's deepening all-IP portfolio, or from upstart domestic players like PurTV. It is a legitimate concern, but one that may be transient. Ultimately, we think all cable operators will see their revenue-split shifting away from TV and towards broadband.

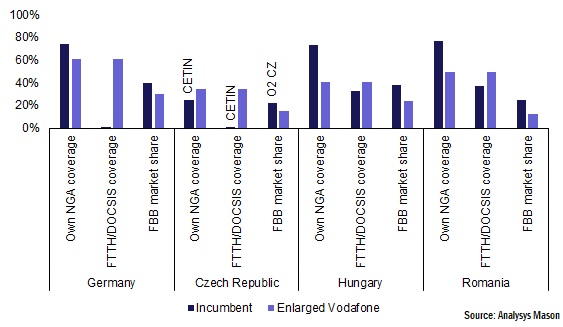

Figure 2: Broadband coverage and broadband market share based on YE 2017, incumbents and enlarged Vodafone

Figure 2 shows the very strong coverage position that Vodafone would have in each of the four markets for FTTP/DOCSIS3.x coverage (in other words, networks capable of gigabit speeds). An enlarged Vodafone Germany will have a higher-capacity fixed network than Telekom with good on-net coverage. By 2022, it claims that it will be able to offer gigabit services to 25 million households (60% of Germany), whereas Telekom has so far committed to little beyond an FTTC upgrade to 35b vectoring. This is probably the bigger worry for Telekom than pay-TV.

It is easy to maintain that the difference between up to 250Mbps (the top speed on 35b vectoring) and a gigabit may not matter much to many consumers now, even though higher speed is a strong marketing tool. But it is much more difficult to claim that it will not matter by 2025, by which time it is highly unlikely that Telekom will be anywhere near 60% coverage with FTTP. It is not surprising then that Telekom appears to set more store by 5G, and potential fixed gigabit wireless, than many of its peers.

What actually happens when two dominant and broadly equivalent scale vertically integrated FMC plays emerge? The Benelux countries offer some insight. In the Netherlands, it looks as if KPN and VodafoneZiggo have limited reasons to compete on quad-play so long as the remaining mobile-centric player (assuming that T-Mobile completes the acquisition of Tele2) does not mount a major challenge based on mobile networks alone. Currently, they offer only similar and modest discounts for quad-plays. In Belgium, where market structure is similar to the Netherlands, the regulator BIPT is taking a tough stance. It judges the broadband market to be uncompetitive, and has demanded symmetrical cost-oriented wholesale broadband access, but this demand has not been made elsewhere and is being challenged in Belgium by both parties.

Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania

Vodafone is currently a mobile-centric play in the three Central and Eastern European (CEE) markets, and the acquisitions will make the market structures in the Czech Republic and Hungary more like those in Western Europe (Romania already has a good level of FMC competition). Mobile-centric businesses look in theory – and in some countries in practice – vulnerable to price-squeezes in the form of integrated operators tariff rebalancing by raising the price of triple-play offerings and reducing the difference between the cost of a triple-play and a quad-play.

However, mobile-centric businesses are not all in trouble, by any means. In CEE markets, which have historically more mobile-oriented and price-sensitive consumers, some mobile-centric operators thrive, and the use of mobile broadband as a substitute in the home is more common. Driving a Western European FMC model may be particularly hard work for Vodafone when it is common to have mobile, broadband and TV from three different providers based on whichever is the cheapest. Breaking this inertia will require lots of incentives, price or otherwise.

After several years of LTE/LTE-A and with C-band becoming part of the 4G/5G ecosystem, mobile networks across Europe are in a much stronger position to replicate fixed/quad-plays than they were a few years ago. Whether they need much more fibre infrastructure for mobile yet is debatable; it helps to own backhaul, but strategic densification of networks is an ever-receding horizon. Higher-order MIMO and 3.5GHz may require similar cell infrastructure to 1800MHz.

In the Czech Republic, the combination looks very strong: Vodafone would be the only integrated player with its own fixed and mobile infrastructure, and it would be dominant in cities. T-Mobile has focused fibre build in smaller towns. Since CETIN and O2 demerged, O2 has more incentive to rely on its mobile network than other former incumbent retail arms, and CETIN's fixed infrastructure is less well developed than that of most of its peers, leaving it in potentially rather a weak position. The fixed market is highly fragmented and underdeveloped, and there are opportunities to consolidate further or simply win customers.

Hungary would look structurally like some Western European markets (two large integrated offering quad-plays plus one mobile-centric), although Telekom will remain by far the largest player. Broadband is less fragmented than in the Czech Republic and has better coverage, so there is no low-hanging fruit for Vodafone, although penetration is a little lower.

Romania is a very different market: three major fibre networks and a highly competitive quad-play market already in place with much lower average revenue per account (ARPA). Vodafone will have reasonable coverage, but it would be late to the quad-play market. Already Telekom and Orange can compete only on value, not on price against Digi, the market leader in broadband, which has just about the lowest prices on the planet: Vodafone will be in the same position.

Downloads

Article (PDF)Authors

Rupert Wood

Research DirectorLatest Publications

FMC will be increasingly important for Belgian MNOs in light of Digi Belgium’s market entry

Article

Higher-income European countries have the highest capex intensities

Article

Fixed–mobile converged bundles pricing: trends and analysis 1Q 2024