FMC dominance and margin expansion: the logic of Vodafone’s acquisition of Liberty Global businesses

09 February 2018 | Research

Article | PDF (4 pages) | Operator Investment Strategies| Fixed–Mobile Convergence| Fibre Infrastructure Strategies

Vodafone confirmed on 5 February 2018 that it was in talks to acquire Liberty Global assets in Europe. The talks appear to exclude Virgin Media (Liberty Global’s main provider in the UK and Ireland). At the time of writing, it looks as if any deals will happen on a country-by-country basis, and that there is no question of a full merger, or of any market-by-market mergers such as the Vodafone–Ziggo merger in the Netherlands. No deals have been reached yet, so this comment is a discussion of the logic and implications of further fixed acquisitions by Vodafone in Europe.

Vodafone wants to be the leader in European convergence

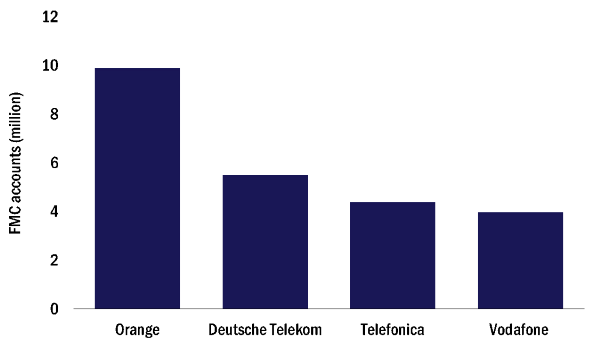

Vodafone’s long-term strategy is to be the only European-level competitor to the incumbents that is of a similar size, in both fixed and mobile, and to have the highest number of fixed–mobile convergence (FMC) accounts in Europe (an ambition shared with Deutsche Telekom and Orange). In 3Q 2017, it was only the fourth (see Figure 1). The acquisition of non-UK/Ireland businesses should propel it to number two.

Figure 1: FMC accounts by operator, Europe, 3Q 2017

Source: Analysys Mason, 2018

Vodafone already has a 10.3% revenue share of European1 mass-market services: mobile, broadband, fixed voice and pay TV (that is, all services excluding enterprise/ICT); this is the largest of any operator. Combining all of Vodafone’s and Liberty Global’s European assets would make Vodafone nearly 60% larger than its nearest rival, Deutsche Telekom. The UK and Ireland are not part of current talks. In continental Europe, Vodafone is currently number three in revenue, but the acquisition of Liberty Global businesses there would propel it to number one.

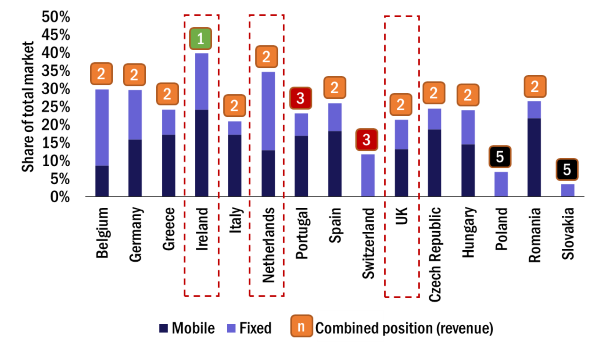

More importantly, at least in the short term, it would be number two in terms of revenue in eight countries, including Germany, Italy and Spain (nine if the existing joint-venture between Vodafone and Ziggo in the Netherlands is included) (see Figure 2). If the Irish business were included (it does not look as if it will be, although until very recently this was a UPC business and not part of Virgin Media), Vodafone would become the largest operator in Ireland.

In fact, this analysis somewhat understates the potential pre-eminence of Vodafone. We see Europe as essentially three differently sized but largely discrete markets.

- Nordic/Baltic zone: other than Three, this is controlled entirely by domestic players. Neither Vodafone nor Liberty Global has a presence here.

- France: a rule unto itself, dominated by four local players. Neither Vodafone nor Liberty Global has a presence here.

- The rest of Europe: telecoms has a much more mixed ownership, and this is where all of Vodafone’s and Liberty Global’s European businesses reside. In this area, either a full combination of Vodafone’s and Liberty Global’s assets, or a combination that left out the UK and Ireland, would give Vodafone a market share of approximately 19%.

Figure 2: Market share, by revenue, of combined Vodafone and Liberty Global assets, Europe, 3Q 2017

Source: Analysys Mason European Telecoms Market Matrix, 2018

Acquisition provides a simple route to where Vodafone wants to be

There are a host of good reasons why combinations of Vodafone and Liberty Global businesses make sense.

- M&A defers the hard work of upselling to the existing base. Building a strong FMC base is difficult if it is done organically and without the kind of disruptive discounting that marked the first wave of FMC in France, Portugal and Spain in the early 2010s. M&A is an admission that gains, in terms of value, are difficult to achieve from convergence, especially if the fixed proposition is based on wholesale products.

- Mobile-centric businesses look in theory, and in some countries in practice, vulnerable to price squeezes, as integrated operators raise the price of fixed triple-plays while keeping the price of FMC bundles steady, thereby reducing the implicit value of mobile services. This form of tariff-rebalancing leaves mobile-centric operators in a position where they have to find ways to replicate fixed services on mobile networks. Cable-based services are, by contrast, more profitable and less volatile than mobile services.

- There is strategic value in owning rather than renting dense fixed assets in a world that will demand more infrastructure, especially as 5G looms.

- M&A is basically about simple cost-cutting. The stated rationale for two recent mobile operator acquisitions of fixed businesses in Europe (T-Mobile Austria and UPC Austria, and Tele2 Sweden and com hem) emphasised the cost-cutting potential as much as the revenue synergies. There is a simple economy of scale in focusing on the household rather than the individual as the basic unit of consumer telecoms: Orange Europe, for one, is moving away from the individual and towards the household. The consolidation of assets may be a simpler and quicker way to expand margins than any form of transformation/digitalisation, the commercial effects of which are not well understood, and which tend to be treated with extreme scepticism by investors.

There are potential downsides to M&A

While we see great potential benefits to combining the businesses, there are risks.

- An increased focus on fixed services brings the threat of more symmetrical broadband regulation. This has already been seen in Belgium.

- Cable services may become overdependent on pay-TV revenue at a time when the pay-TV model is under threat from pure IP video service providers (though European cable is less dependent on such revenue than cable in the USA).

- Cable is not an ideal underlying transport infrastructure for 5G if it requires dense small-cell deployment, whereas fibre is.

- Such an acquisition would cause Vodafone to extend its debt ratio.

- Without further acquisitions, the fixed-only markets of Poland, Slovakia and Switzerland look unattractive as acquisition targets, even though each of these countries has MNOs that are not part of major groups: O2 Slovakia, Play, Polkomtel, Salt and Sunrise.

If the UK businesses are not part of any deals, it clears the way for other M&A

At the time of writing, Liberty Global’s UK/Ireland business, Virgin Media, was not part of the discussions between Vodafone and Liberty Global. If there is no acquisition (either way) between Virgin Media and Vodafone UK, the UK will remain with O2, Three and Vodafone as mobile-centric businesses,2 and Virgin Media, Sky and TalkTalk as fixed-centric businesses. This looks increasingly odd in a world with a decreasing number of mobile or fixed pure-plays. Indeed, we have already speculated that Sky will have no long-term reason to hang on to its broadband and mobile businesses.

If a Vodafone–Virgin Media deal does not materialise, then Vodafone buying Sky’s telecoms business would make sense as a way to bulk up Vodafone’s tiny UK broadband share (1.2%), possibly with a cross-selling partnership between Vodafone and Sky. Additionally, O2 is always potentially up for sale. As such, Liberty Global could acquire O2 with the proceeds from a European sell-off.

1Europe: EU28 + Norway and Switzerland.

2Vodafone’s recent agreement with CityFibre for FTTH would be unaffected.

Downloads

Article (PDF)Authors

Rupert Wood

Research DirectorLatest Publications

FMC will be increasingly important for Belgian MNOs in light of Digi Belgium’s market entry

Article

Higher-income European countries have the highest capex intensities

Article

Fixed–mobile converged bundles pricing: trends and analysis 1Q 2024