Facebook will integrate its services to ramp up its monetisation efforts

Facebook’s forthcoming integration of the infrastructure of its Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp services is another sign of the company’s desire to monetise as much of its customer data as possible and to cement its leadership in the messaging space. This article will explore Facebook’s strategy, provide information about what the move means for rivals and outline the changing landscape for messaging services.

Facebook’s expansion has hindered rivals

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said, during the company’s 4Q 2018 conference call in January 2019, that Facebook will integrate the technical infrastructure of its messaging apps, thereby allowing users to talk to one another across platforms.1 He said that he wants to bring WhatsApp’s encryption functionality to the other apps; this is no surprise given the company’s defensive attitude regarding user privacy.

The announcement may have come as a surprise for some, but Facebook gave an early hint at what was coming in April 2018 when it updated its terms of service. It outlined a “one company” policy and noted that Instagram, Messenger, Oculus (Facebook’s VR arm) and WhatsApp all shared “services, infrastructure and information”.2 WhatsApp’s terms of service state that information is not used to provide more-relevant adverts on Facebook,3 but by adding “today” at the start of that statement and throughout the terms, the company suggested that what happens today may not be the case tomorrow.

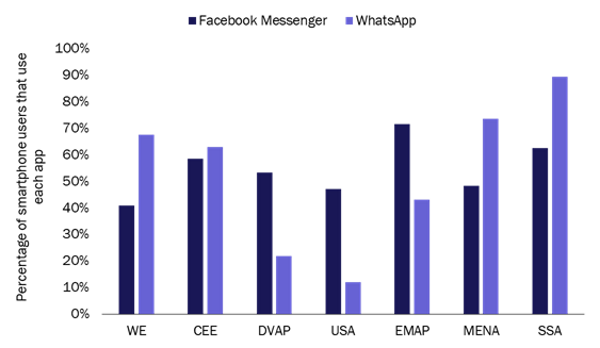

Around two billion people worldwide (over a quarter of the world’s population) use at least one of the core Facebook services (that is Facebook, Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp) daily.4 However, the popularity of these services varies across different regions. WhatsApp dominates in Western Europe but is much less used in the USA, as shown in Figure 1. According to Analysys Mason’s Connected Consumer Survey, Messenger is the preferred Facebook chat service across emerging Asia–Pacific and developed Asia–Pacific. Facebook usage is consistent around the world, with a few important exceptions (such as China, where it is blocked); Instagram penetration is higher in western, developed markets.

Figure 1: Penetration of Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp among surveyed smartphone users, by region (selected countries only), 3Q 2018

Source: Analysys Mason, 2019

Facebook’s strategy has been to remove its competition from the market: instead of competing with Instagram or WhatsApp, it bought them. It has also been growing at the expense of other services in Asia. Several years ago, companies such as LINE and WeChat had the necessary ambitions and resources to build on their domestic successes and become global players, but they have had to scale back their expansion plans. In Indonesia, for example, LINE’s smartphone user penetration fell from 40% to 25% between 2016 and 2018, whereas the same metric increased from 61% to 87% for WhatsApp and 34% to 50% for Messenger. WeChat has focused on catering to Chinese communities in the emerging Asia–Pacific region rather than recreating its domestic success in new markets.

Facebook’s integration plan shows its desire to keep users within the Facebook ecosystem

Facebook continues to grow its user base. The number of both daily and monthly active users increased by 9% during 2018, despite fears that it could plateau after a minor decline in Europe and the USA earlier in the year.5 However, the company is placing a greater strategic focus on deepening the engagement with its user base and the integration of its main apps should encourage ‘cross-selling’ between services.

The move also increases Facebook’s stickiness by encouraging customers to use its apps for longer. Being able to communicate between Instagram and WhatsApp, for example, keeps users within Facebook’s ecosystem without any friction and prevents them from spending time on rival apps. This will help to generate more data and to increase advertising revenue, especially if it forces Instagram and WhatsApp users to combine their accounts into one (this is not currently a requirement).

Facebook’s decision to combine its apps could also be motivated by the concerns about its monopolistic grip on social media. If it were to fall foul of attempted antitrust action, regulators would be faced with the challenge of working out where one app begins and another ends, which could work in the company’s favour. However, the move could also lead to the following new problems for Facebook.

- Instagram and WhatsApp (that have avoided the negative publicity associated with Facebook) may be damaged from being more-closely tied to the parent app.

- The unified infrastructure may add to existing concerns over how much data Facebook gathers and by what means it does so.

- More-repressive regimes may become unhappy that Facebook will now offer end-to-end encryption for all services.

Facebook seeks to dominate social apps with its “one company” policy

Facebook’s move will take its one company policy to its logical conclusion; it will create even more of a walled-garden experience and will potentially protect it from a break-up of its services through antitrust practice. It is seeking to move past the privacy scandals of recent years by becoming even more competitive.

Many of Facebook’s rivals have already moved away from social media in order to focus their efforts on alternative consumer interfaces. Google continues to have a strong presence on smartphones (with Android OS, the YouTube app and the Chrome browser) but recognises that it has lost out to Facebook on social and communications services, as is the case with Apple. Both of these companies are using their strength in operating systems to expand their presence across a range of consumer devices (such as the set-top box and TV). Google is also addressing the emerging market of in-car infotainment and has plans for a native Android platform for cars.

The voice interface and digital assistant space has become highly contested recently, partly due to the emergence of a new hardware category: the smart speaker. Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri and Google’s Assistant are increasingly present in service discovery and consumption. Facebook, too, is active in the market, though it discontinued its virtual assistant, M, in 2018, and was late to the market with its Portal smart display device (launched in October 2018). Facebook’s one company policy appears to be an attempt by the company to focus on its core business in order to ensure its continued global success in the social media space.

1 Facebook (30 January 2019), Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2018 Results Conference Call. Available at https://s21.q4cdn.com/399680738/files/doc_financials/2018/Q4/Q4-2018-earnings-call-transcript.pdf.

2 Facebook, We’re making out Terms and Data Policy clearer, without new rights to use your data on Facebook. Available at https://en-gb.facebook.com/about/terms-updates.

3 WhatsApp, How we work with the Facebook Companies. Available at https://faq.whatsapp.com/general/26000112/?eea=1.

4 Facebook Investor Relations (30 January 2019), Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2018 Results. Available at https://investor.fb.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2019/Facebook-Reports-Fourth-Quarter-and-Full-Year-2018-Results/default.aspx.

5 Facebook (30 January 2019), Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2018 Results. Available at https://s21.q4cdn.com/399680738/files/doc_financials/2018/Q4/Q4-2018-Earnings-Release.pdf

Downloads

Article (PDF)Latest Publications

Major CPaaS players are struggling financially, which will threaten their capacity to invest in new areas

Article

Operators will still lead the mobile voice space, but RCS will have a limited effect on the messaging market

Article

AI series: AI adoption can offer SMBs an edge over larger companies