Interconnection is the glue that holds the internet together

The internet is part of our everyday lives. We rely on it to communicate, work and entertain ourselves. But how does internet traffic get from one point to another? How did clicking on a link bring up this article? Interconnection is the answer. What is it, how does it work and what does our seemingly insatiable appetite for content mean for its future?

The internet is a global network of networks. A network, in this context, being a system that connects two or more computers or devices to share resources, exchange data and communicate. These networks can vary greatly in size and can be owned by companies, universities, research institutes and governments. Interconnection is the glue that holds these networks together and enables anyone to reach any point on the internet.

When the US government decommissioned the NSFNet backbone and left the internet to commercial forces on 30 April 1995, interconnection arrangements were needed so that networks could exchange internet traffic. These agreements emerged from voluntary negotiations between network owners and have adapted as the internet evolved over the past 30 years.

The internet has undergone significant changes since these commercial beginnings. It has grown at a remarkable rate, globalised from its historical roots in the USA and the volume of traffic has increased exponentially as new content and services have emerged. Content providers today, such as Google and Meta, often deploy their own networks to deliver their content to users worldwide. One constant among the changes is that commercial negotiations, rather than regulation, have shaped interconnection arrangements.

Interconnection arrangements ensure traffic moves from one point to another

There are two main ways networks connect: ‘peering’ and ‘transit’. Peering is when two networks exchange traffic with each other, and transit is when a smaller network buys access to a larger network. These connections can happen in private facilities, data centres or at public locations called internet exchange points (IXPs).

In the early days, internet service providers (ISPs) could easily exchange traffic with each other through peering. Since they were similar in size, scope and the amount of traffic exchanged – in other words, peers – the exchange of traffic was generally ‘settlement free’, with no payments made. This is still true today for most peering arrangements.

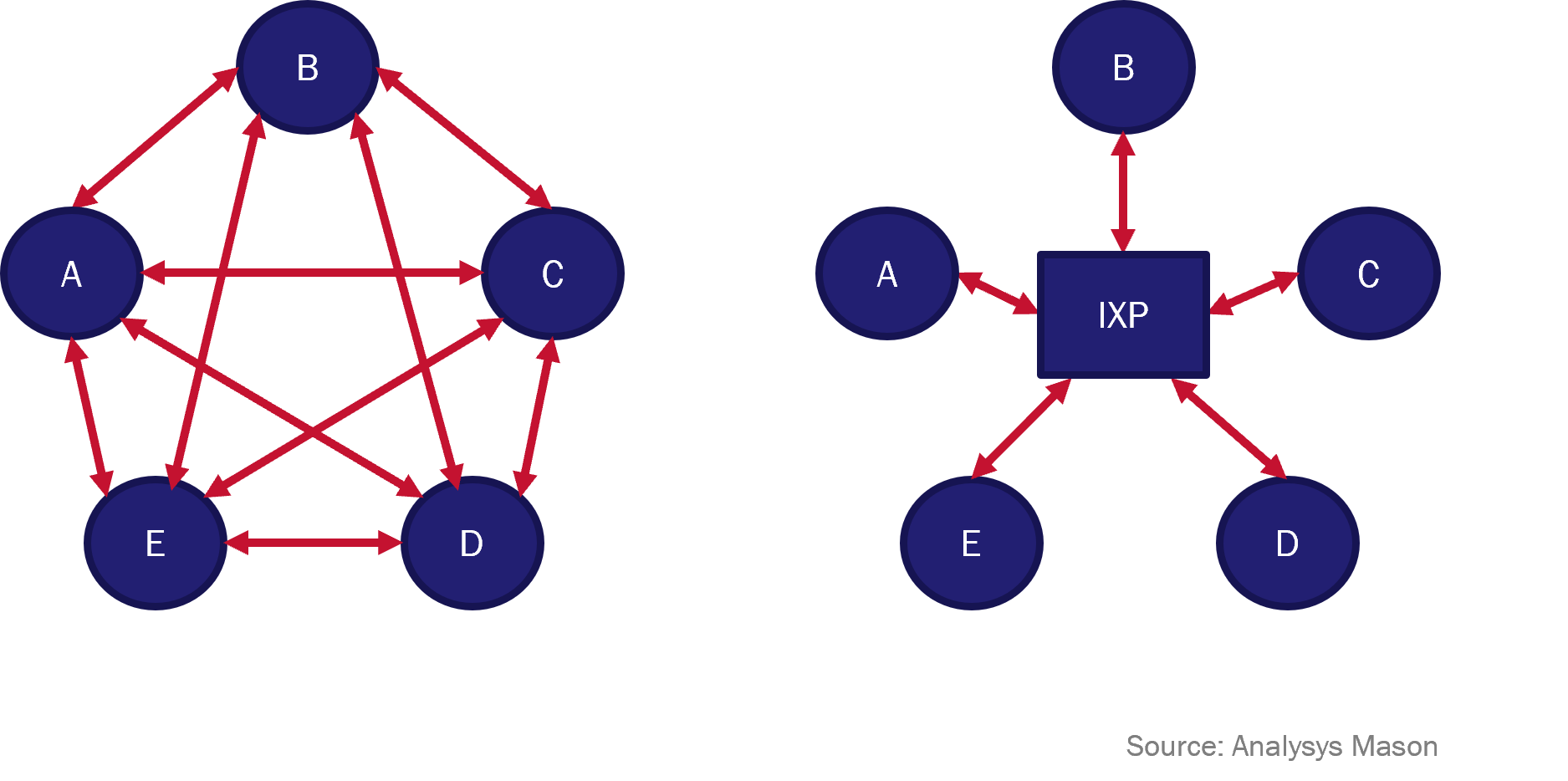

As the number of networks grew, it soon became impractical for each network to directly connect with every other peering partner. This led to the development of IXPs, which serve as central locations for interconnection where networks can exchange traffic using just one connection, rather than one link per peer, as shown in Figure 1 below. IXPs quickly grew in number and spread around the world as the internet expanded.

Figure 1: Peering network versus IXP

As business models changed and larger providers appeared, shifting the ‘peer’ dynamic, smaller ISPs needed a way to provide their customers with access to the entire internet. So, they started using wholesale arrangements known as ‘transit’ – where the smaller entities pay larger ISPs to reach the rest of the internet they could not otherwise reach.

Effects of the content explosion

Disputes between providers over interconnection have existed for as long as peering itself, despite the ever-increasing number of IXPs and peering arrangements. As content on the internet has shifted from text to multimedia, some ISPs started receiving more traffic than they were sending, especially from providers of streaming video services. The ISPs therefore claimed they should be paid for delivering the content to their subscribers. In response to the claims of the ISPs, content providers began using content delivery networks (CDNs) to store content closer to the ISPs. This reduces the ISPs’ cost of delivering content to their subscribers because it takes less of their network resources, and it also speeds up the delivery of the content because it is closer to the users.

Emerging attempts at regulation

Some ISPs in Europe have suggested that large online platforms, like YouTube, should pay their ‘fair share’ of the deployment and operating costs of internet access networks. They argue that because these platforms generate a significant amount of internet traffic, they should help cover the costs by paying network usage fees to the ISPs for delivering that traffic. Although this idea has not yet been adopted in Europe, it is being considered by other countries including Brazil.

As the internet has globalised and grown in usage, interconnection arrangements have evolved organically. Governments are studying these changes against the backdrop of a push for regulation. The current commercial arrangements are evolving and working well, enabling the emergence of new business models such as CDNs. Any regulatory intervention could lock in place the status quo and restrict future traffic and business models from emerging.

Do you know the internet?

Author

Michael Kende

Senior AdviserRelated items

Client project

Developing a go-to-market strategy and a first-of-its-kind business case for an Asian telecoms operator’s entry into the GPUaaS market

Podcast

TMT predictions 2026: operators are at a crossroads

Predictions

GPUaaS revenue will quadruple in the next 5 years, powering new data-centre investment opportunities