Wireless traffic forecasts: 5G will make little difference to long-term trends

Listen to or download the associated podcast

Analysys Mason’s Wireless network data traffic: worldwide trends and forecasts 2020–2025 is the first traffic forecast that we have published since the launch of 5G. We still expect that 5G will change the general direction of traffic growth. Some of the other high-level findings from the report are as follows.

- Mobile data traffic will grow in a broadly linear manner worldwide between 2019 and 2025, by a factor of 5.5.

- 5G traffic will not dominate as quickly as 4G traffic did, but it will overtake 4G traffic in 2025 (if fixed-wireless access (FWA) is included). 5G handset traffic will be similar to 4G handset traffic in 2025.

- A growing proportion of handset traffic will use cellular networks. Cellular networks accounted for 39% of all handset traffic worldwide in 2019 (with huge variations between countries), but it will be close to 50% by 2025. This trend will be reversed in countries with rapidly expanding fixed broadband penetration.

- The average cellular network usage by handsets worldwide will grow from 5.4GB per month in December 2019 to 19.7GB in December 2025. The average data usage by handsets on all networks worldwide will grow from 13.5GB per month to 40.5GB per month over the same period.

- FWA will account for 13% of all cellular traffic by 2025. Of this, handsets and data-only devices will account for 80% and 7%, respectively.

- The Wi-Fi share of the total IP access network traffic will increase from 53% in 2019 to 66% in 2025. The cellular share will rise from 12% to 18% over the same period.

Analysys Mason has long predicted that 5G will not bring about particularly profound changes to the general long-term trend in mobile traffic (where ‘mobile’ here excludes FWA); that is, we expect that the cellular traffic growth rate will decline and eventually converge with the overall IP traffic growth rate. The report summarised here explains this in more detail.

5G is likely to lead to only short-term surges in traffic

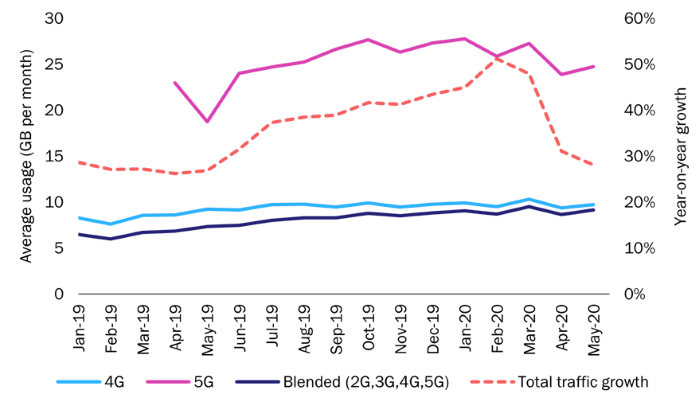

Coverage is still very limited in some of markets in which 5G has been launched, but 5G does introduce a huge block of additional capacity to cellular networks. In the past, we have observed that mobile traffic volume is primarily a function of supply and pricing, and not of extrinsic demand: volumes rise quickly when supply is plentiful, and slowly when it is constrained. However, we have also seen that new capacity or generations of networks and new pricing (which often go hand-in-hand) have, over time, created increasingly weak surges in traffic. This effect was seen in South Korea (Figure 1); the year-on-year traffic growth rate picked up after the 5G launch in April 2019, but has since fallen back to the levels seen prior to the roll-out.1

Figure 1: Mobile data usage by generation and the total year-on-year mobile traffic growth, South Korea, January 2019–May 2020

Source: Analysys Mason from MSIT, 2020

Cellular data usage will proportionately start to displace Wi-Fi usage on handsets, but not on any other devices

Increasingly common and inexpensive unlimited data contracts are dampening Wi-Fi usage on handsets in both public Wi-Fi spaces and, much more importantly, private Wi-Fi networks (home or office). The Wi-Fi share of handset data varies greatly between countries depending on mobile pricing and home broadband take-up, but it was 61% worldwide in 2019. We forecast that this will fall to 50% by 2025. This is a fairly slow decline; although unlimited data contracts stop disincentivising the use of cellular networks, they do not actually incentivise their use. Wi-Fi will continue to be the dominant radio access technology in terms of the overall traffic (there is currently four times more Wi-Fi data traffic than cellular traffic) for two reasons: other, more bandwidth-demanding, wireless devices rely solely on Wi-Fi, and fixed gigabit broadband plus Wi-Fi6 should provide a superior indoor experience to 4G or 5G.

5G illustrates the perils of overproduction

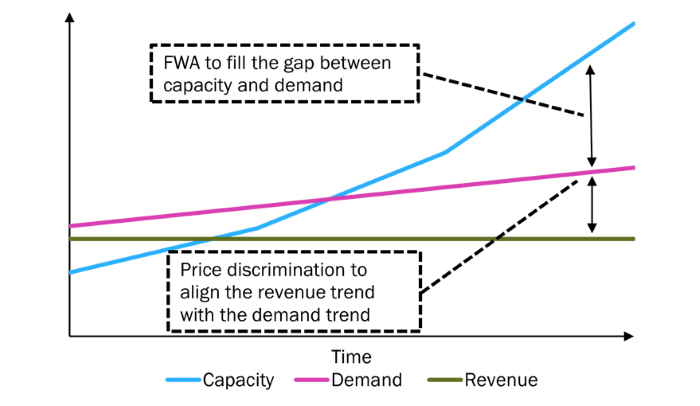

5G launches are showing some characteristics of a crisis of overproduction. Operators are caught between finding (or creating) high-yield use cases (often with more-complex value chains) to justify the investment and falling back on high-volume, low-yield ones. Simple mobile handset usage is not going to change MNOs’ fortunes, as most acknowledge; hence their interest in novel (often B2B) use cases outside eMBB, particularly the idea of ‘permission-in’ network slices sold at, we must assume, highly differentiated rates that generate higher yields per gigabyte than end-user-pays best-efforts internet. It is too early to predict the impact of these new use cases on traffic, but of course the volume of traffic is not the critical factor in these cases. The development of these new use cases may be understood as a kind of price discrimination to make the revenue trend (which is normally flat) match the demand trend more closely; that is, to give moderate and broadly linear growth (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Capacity, demand and revenue in a crisis of overproduction

Source: Analysys Mason, 2020

Source: Analysys Mason, 2020

If cellular traffic volumes show that consumers are fundamentally underwhelmed by 5G and find little to do on 5G that they could not already do on 4G, then we expect that some MNOs will use FWA to monetise their investments in spectrum and the newly expanded, yet empty airwaves. A specific set of conditions is required for FWA to thrive; namely, poor coverage and weak competition from gigabit-capable fixed broadband. Where these conditions are not in place, there is no fixed-to-FWA substitution. The opportunity for FWA may be slipping away in countries in which there has been significant investment in fibre, and is almost non-existent in super-advanced telecoms economies such as China and South Korea. Nevertheless, we expect that the adoption of the ultimate ‘pile-it-high-and-sell-it-cheap’ cellular service, FWA, will pick up in a few markets, most notably in the USA, but also in Australia, Germany and the UK. Indeed, we forecast that it will represent 13% of cellular network traffic worldwide by 2025.

Predicting that 5G traffic will catch up with 4G traffic by 2025 may appear bold. In fact, we do not expect that it will dominate quite as quickly as 4G did, but neither do we envisage that operators, having invested large sums in 5G, will allow the networks to lie fallow. The real problem for MNOs is whether these networks get filled with the right kind of traffic.

1 COVID-19 muddies the waters, because in this case it is impossible to tell whether the pandemic caused the stronger growth in early 2020 or the slower growth in mid-2020. Most MNOs saw an increase in cellular traffic during lockdown, but a significant minority saw a decrease.

Download

Article (PDF)Author

Rupert Wood

Research Director, expert in infrastructure, fixed networks and wholesaleRelated items

Forecast report

Wireless network data traffic: worldwide trends and forecasts 2023–2029

Article

mmWave spectrum developments in South Korea continue to be turbulent

Strategy report

Investing in FWA or buying FTTP wholesale: a comparison for mobile network operators